On Tuesday, Feb. 4, Sulphur Springs Mayor John Sellers and City Manager Marc Maxwell announced their intentions to share findings of independent soil testing with citizens regarding Helfferich Hill on the former Thermo mine property.

“There’s so much disinformation,” Maxwell said.

“We encourage, because we knew what the answers were,” Sellers told the citizen audience. “The soil sample was another layer of us to show what was there.”

With that, the council voted unanimously to annex the nearly 5,000 acres, which will approximately double the size of the city limits, according to Maxwell.

All is far from complete regarding the property, though.

Starting in March 2017, Luminant entered into a lengthy back-and-forth with the Railroad Commission that continues to this day, regarding the county’s new tallest topographical feature, Helfferich Hill. Specifically, Luminant and the city want the hill to remain, and the Railroad Commission wants the hill gone.

The two sides could not come to a compromise despite round after round of forms, revisions and applications, and the final decision now lies with an administrative law judge.

CONTENTIOUS DIRT

Throughout most of Hopkins County’s history, indigenous people and settlers alike knew the grove of sandy soil where blackjack oaks grew was the highest elevation around. Navigation Vertical Datum confirms that the middle of Cumby, a whopping 646 feet above sea level, is the county’s highest point. With the addition of Helfferich Hill rising up out of the grassland, the Railroad Commission felt weary of Luminant and the city’s insistence that it should stay.

In October 2018, the city and Luminant prepared a “development agreement” regarding the property. This allowed the city to take over the property provided that Luminant would be granted access to the property at any time, for any reason, and outlined numerous other conditions.

The city could not create zoning ordinances that prevented Luminant from remitting the final sections of the land or prevent Luminant from building any streets, roads or other infrastructure they might need to do their final work cleaning up the pond, coal debris or machine shed.

Although the city was not required to supply financial support to Luminant and Luminant was responsible for all their own costs, if the city wanted to, say, take over Luminant’s on-site wastewater treatment facility, the city would be financially responsible for applying for their own permit from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ).

The city and Luminant in this document both seemed clear on what they were getting: a property to “flexibly develop, use and maintain … as a multi-use site for its [the city’s] residents” to include future recreation and commercial areas with “walking trails, bike trails, picnic areas and picnic furniture, playgrounds, pavilions and parking areas.”

It was signed in March 2017 by Luminant Vice President Matt Goering, Sellers, Maxwell, then-council member Emily Glass and city attorney Jim McLeroy. It all hinged on the final approval of the Railroad Commission, and Luminant estimated in their development document it would take five to seven years for that to occur.

According to this estimate, the city should be looking at a projection of 2020 to begin construction on some parts of the Thermo property at the earliest, or 2027 at the latest.

In July 2017, Luminant submitted to the Railroad Commission their designs for reclamation of Area H (later called Area D1), which contains the temporary pond and Helfferich Hill. The major departure, leaving in place 2 million cubic yards of dirt, was not a significant revision to their original plan, Luminant said.

The cost both to move the hill for Luminant or to reconstruct the hill for the city if it was ultimately torn down would be “in the millions,” Maxwell said, although he could not estimate a more specific cost.

Responding on Dec. 5, 2017, director of the Railroad Commission’s Surface Mining Division Denny Kingsley told Luminant environmental director Sid Stroud that after seeking a legal opinion from the RRC’s Office of General Counsel (OGC), he necessarily advised that the variance was significant.

Luminant provided additional information Feb. 15, 2018 and requested that Kingsley rescind his finding of significance. Luminant and Kingsley met May 1, 2018, and Kingsley requested a legal opinion from the OGC once again July 18, 2018. Luminant provided additional documentation Aug. 9, 2018, which Kingsley gave to the OGC. By Aug. 31, 2018, OGC staff urged Kingsley to uphold his finding of significance, which he did and notified Stroud in a Sept. 21, 2018 letter.

The Railroad Commission provided Luminant with a list of staff recommendations about why they found the company’s application “deficient.” First on the list was Helfferich Hill.

“Luminant does not indicate why it proposes to leave an approximately 120-foot high temporary, unsuitable-material stockpile … as a permanent structure,” RRC staff said.

The staff was also concerned by the “rills and gullies” present on the hill and wanted Luminant to establish better vegetative cover on the hill.

On Aug. 31, 2018, Luminant outlined that they did not believe their variance request was legally significant as the definition of significance is that it affects living persons — and no one lives on the Thermo property.

On the hill, however, Luminant did not want to budge.

“The city expresses its desire to develop, use and maintain … a multi-use recreational property with recreational and commercial uses,” Luminant told the RRC. “Luminant and the City have consulted with the RRC over 12 months. … The contours of the slope … support the long-term development goals of the city.”

“It is a crucial aspect of the city’s developmental plans,” Stroud stressed.

In May 2018, after a year and two months of legal tête-à-tête between Luminant and the RRC, Maxwell made the journey to Austin to testify before the RRC. In a text that the Texas Tribune says shows that Luminant head honchos coached Maxwell on what to tell the RRC, Thermo site director Del McCabe tells Maxwell, “Marc, I believe a key message the RRC needs to hear tomorrow is your needs.”

“I believe the H-area hill [Helfferich Hill] will bring up the most questions, but I would stress it will be used as the foundation for a future amphitheater and entertainment complex. Good luck tomorrow,” McCabe wrote.

Maxwell contends he was not coached.

“If anything, I coached them,” Maxwell said. “In fact, we had a meeting again in the cafeteria right before we went up. That’s how collaborative government works.”

“Staff is dug in,” Maxwell opined. “Usually staff talks through and works though, but at this point, they’ve just said no and they’re going to work it out with the administrative law judge.”

Stroud told the News-Telegram it was fairly common for the RRC and Luminant to go through a lengthy process regarding revision processes.

“We wanted the staff at the RRC to understand that we wanted this,” Maxwell said. “We are the driving force: We want the property. We want the hill to remain.”

At this time, no final decision regarding the hill has been made, according to RRC spokesperson Ramona Nye. The reclamation proposal was deemed significant and is now a pending docket in the RRC’s Hearings Division, Nye said.

A ruling by an administrative law judge is final. Maxwell says the city will deal with whatever decision the administrative law judge reaches.

“Even if we get to keep half of the hill, that would still be something,” he said. “Better to own it with a hill than without, but if no hill, that’s okay.”

Nye did not answer questions about how the RRC came to believe there were toxic or acid-forming materials in Helfferich Hill. (See related story “Thermo Pt. I” in the Saturday, Feb. 1 edition of the News-Telegram.)

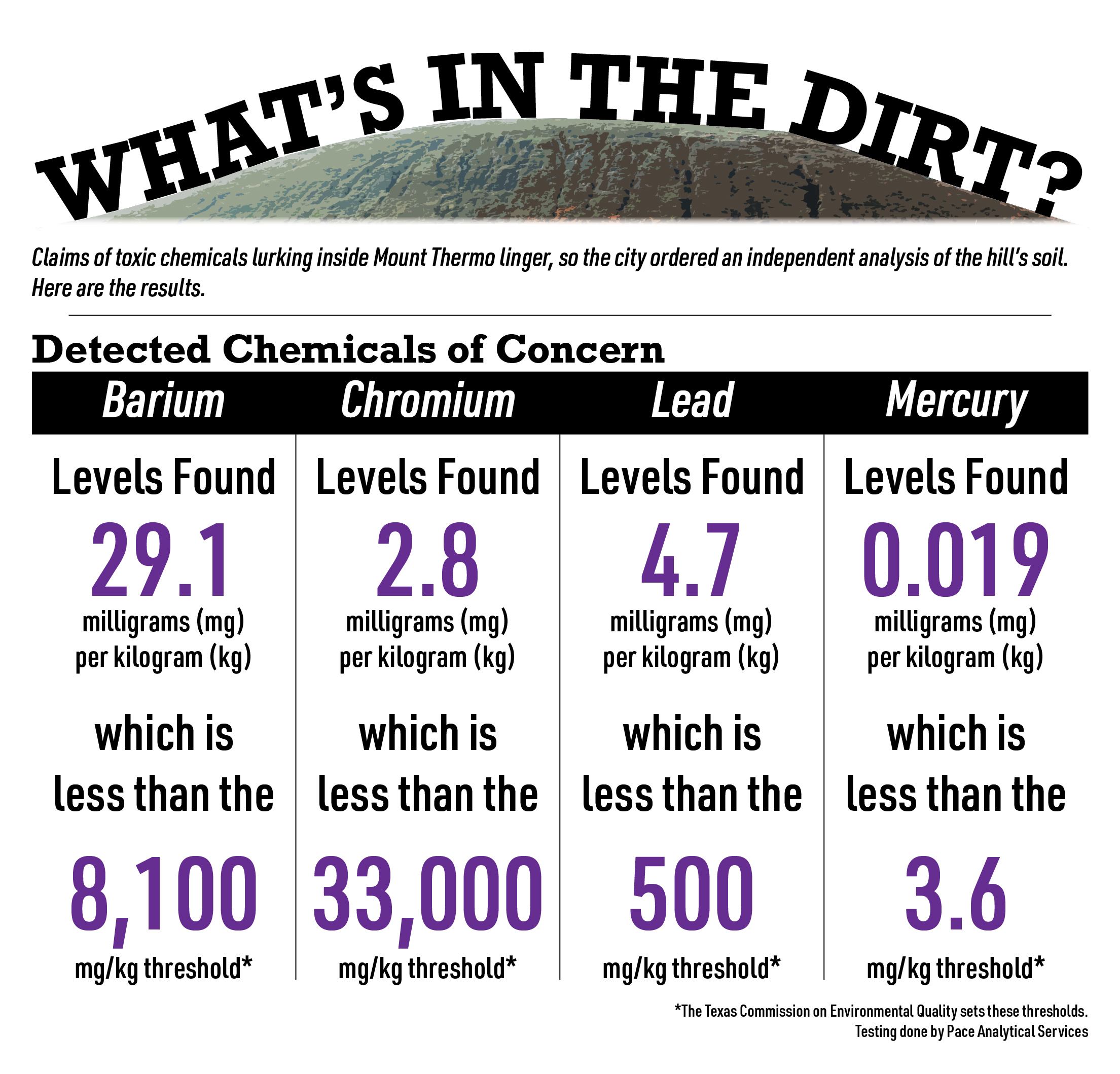

According to independent testing by the city, microscopic levels of contaminants exist within the Helfferich Hill, and the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) would permit homes to be built within the area. For example, TCEQ allows 3,300 milligrams per kilogram of chromium for home sites, and Helfferich Hill had 2.8 milligrams per kilogram. For lead, TCEQ allows 500 milligrams per kilogram, whereas Helfferich Hill had 4.7 milligrams per kilogram.

Many contaminants show no detectable levels in Helfferich Hill, such as arsenic, cadmium, selenium and silver, according to independent testing.

Pesticides and volatile organic compounds were also not present, according to independent testing. Soil acidity by independent testing measured at 6.7, which is closer to neutral than testing the News-Telegram completed in which the measurement was a pH of 5.98.

A BRAND NEW CITY

The Thermo property is composed of areas A through H, ranging from 100 to over 1,000 acres, according to map data. Areas A1-A3 have already been through proposal, approval and reclamation and are free of obligation to the RRC, according to map data. (See map, page 14 A.) This does not mean they are ready for the city to build, however.

Because each area was mined and reclaimed at a different rate, each area will come off bond and be ready for the city to break ground in different years. For example, the A-1 area was the first area to be mined in 1978. It was exhausted of its lignite supply in 1979, according to previous News-Telegram reports from 1979, and began its reclamation process in 1980. It is the earliest parcel at which the city can expect to start construction, approximately 2020, according to map data.

Area D1, which contains Helfferich Hill, is not even out of the courts and does not have a definitive deadline on its reclamation. Maxwell doubts that it will. If it follows the general timeline of Area A-1, citizens can expect construction near Helfferich Hill in 2027 at the earliest, according to city estimates. However, 2027 is not solid, as no one knows when the administrative law judge will reach a decision.

Maxwell has previously stated that he would like the A-1 area, approximately 1,000 acres, to become a business park. According to Economic Development Corporation Executive Director Roger Feagley, space for businesses in Hopkins County is at a premium.

Sulphur Springs currently has two business parks: the Pioneer business park at 103.05 mainly grassland acres and the Heritage business park at 117.33 mainly grassland acres, according to city land data. The Heritage and Pioneer business parks are currently home to Summit Manufacturing, Armorock Polymer Concrete and others, but Feagley is running out of space to offer new businesses, he says.

“One of the good things but also one of the bad things is that we’ve been fairly successful at bringing new business into town,” Feagley said. “Because of that, we’re running out of land.”

The addition of the Thermo property would seem like a silver bullet for the EDC, but Feagley said he has always worried that “free land may be too expensive.”

“It’s going to need a lot of infrastructure,” Feagley said. “There’s no water, no sewer, no improved roads.”

The addition of a twolane road costs approximately $300 a linear foot, Feagley said. This does not account for the water and sewer lines beneath it, which add another $100 to $150 per linear foot. Multiplied over the area of approximately 7 square miles, the cost quickly reaches millions.

This poses a challenge for Feagley, who bases a large portion of his sales pitch to future companies on a principle he calls “development follows infrastructure.”

“When you look at a piece of land and it doesn’t have the road or water or sewer in there, it’s hard to get a customer to see that vision,” Feagley said. “Once you have the infrastructure, a customer will come up there and they’ll say, ‘Everything I need is here, I just have to move the building.’”

The only existing utilities on the site are a 2-inch water line which was installed to provide mine workers with drinking water, Feagley said, as well as some mining roads that have been maintained in various conditions.

The city has budgeted from $50,000 to $150,000 to develop a site-specific plan for the property, according to the Parks and Open Space Master Plan, but it depends upon who you ask in regards to who will pay for the infrastructure itself.

According to Maxwell, the EDC should foot the bill for the development of their thousand-acre business park through sales tax, which is how the EDC budget is generated.

“When you’re talking about industry, it’s a whole different ball game,” Maxwell said. “The property tax revenues generated in any subdivision are insufficient to maintain its infrastructure. … An industrial park gets my attention. The tax revenue generated by those is far greater.”

Feagley would like to use the existing rail to generate revenue is a promising route to funding for infrastructure, but he calls it a “catch-22” as the area that contains the rail does not come off-bond with the RRC until the year 2022. The area connecting the railway to the road doesn’t come off bond until 2025, further complicating possible revenue streams, Feagley said.

Yet if the process the city has gone through with Helfferich Hill is any indication, the RRC has not demonstrated they are willing to take the city’s desires into consideration during their legislative process.

Whatever the plan is, Feagley says, the city needs to go big. The EDC hopes to draw in the “once in a lifetime” $100 million business which could take up as many as 400 acres of space, Feagley says. This represents approximately double the size of the Saputo facility, according to Feagley. Maxwell also feels confident, saying the city is “doing the dance” with several large companies regarding occupying the property.

Niewiadomski says it’s far too early to tell how infrastructure costs will play out.

“At this point, we’re jumping way ahead,” he said. “We’ve been doing some preliminary studies of the site to look at suitability, and that’s the first thing. Initially, we have to determine where it’s suitable to build. Then we look if there are any existing utilities that can serve it, and that will all be part of a master plan.”

Niewiadomski says a master plan for Thermo is another two years in the making.

“It’s like a clean slate to build a brand new city,” Niewiadomski said.

DREAMS TO REMEMBER

In the waning light of the winter sun, most of the Thermo property looks as close to unmarred by human intervention as it did when white settlers arrived in Hopkins County some 200 years ago.

The red-tailed hawk perches in the bare dogwood branches. Black and pintail ducks gather in the lakes, even the Caribbean-colored temporary pond which is supposed to be too acidic to support life. Fresh tracks in the clay mark the trails of deer, coyotes and raccoons. If it weren’t for service roads through the pines and the occasional wire fence, one would never know of a human presence at all.

Maxwell describes the satisfaction he gains from looking out over the unaltered vista as “immense.” However, turning the expanse into something the city can also be proud of will be Maxwell’s biggest challenge yet, he says.

“Nobody knows what Thermo is,” Maxwell said. “Nobody’s ever been out here; it’s all conjecture. At least with downtown they could go see it. Until the results come and everything is getting paved and reconstructed, this will be harder.”

And, he says, he’s tired of being known as “The Downtown Guy.”

“Yeah, I’m Mr. Downtown and all, … but to me, the project itself is a thrill,” Maxwell said. “I’m extremely results-oriented. … Isn’t that the point, to get results? I live for that.”

Maxwell’s biggest dream, he says, is for the city to become financially independent and free from debt.

“The clincher for me is to grow or not to grow,” Maxwell said. “Probably some time after I retire, it’s going to happen. The question is, are we ready for it when it gets here?”

The city currently has plans in place to try to deal with the growth it can handle, Maxwell says. Passed by the city council in 2018, the Street Improvement Plan charges citizens $5 yearly and has already repaved approximately 5.5 miles of city streets. Citizen John Lambert pointed out a catch to the city council: the streets have never been redone at a rate faster than they are decaying. Maxwell did not contest Lambert’s point; in fact, he agreed.

“It’s all fun and games while you’re growing and the streets are new and the water lines are new. There’s no maintenance to be done and the money’s coming in and it’s all great,” Maxwell said. “Go over to Mesquite and Garland and see how they’re coping. The bill is due, and they’re standing with their shoulders shrugged asking, ‘What do we do?’”

This is why, according to Maxwell, monetizing the Thermo property will set the city up to be financially independent in the future.

“We have pretty good bones in this city. We’ve made mistakes, but not a lot,” he said. “My biggest dream is to retire and have the taxes from the property [Thermo] alone fund our capital improvements.”

“There’s probably three ways to do it right and 5,000 ways to do it wrong,” Feagley agreed. “Before we make a mistake, since we’re talking millions and millions of dollars, let’s all agree that this is what we want to do.”

Dozens of different concepts for the property are in the nascent stage: mud run obstacle races, bird dog field trial courses, hike and bike trails, parks, playgrounds, fishing lakes, duck hunting grounds, housing, RV campgrounds, and not least a kidney bean-shaped amphitheater where Helfferich Hill now sits. Feagley, Maxwell and Niewiadomski call for inclusivity on the part of city council, citizens and businesses over the next years as dreams become reality.

“There really is something to the whole legacy idea,” Maxwell said. “I’d like to know when I’m done here that I was productive and I made a difference.