Steed family continues 1986 search for missing father, husband

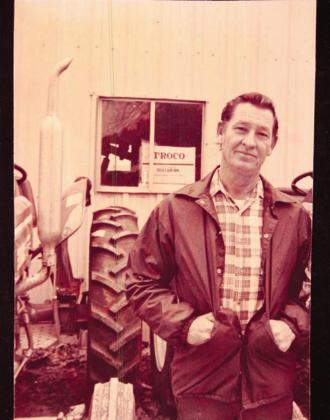

When detectives in Williamson County identified 31-year-old remains as missing Sulphur Springs teen Sue Ann Huskey, Jennifer Steed Adams wanted to remind residents that another Sulphur Springs citizen is missing. Her grandfather, A.W. Steed, has not been seen since Aug. 31, 1986.

That mild labor day weekend, the Steed family was planning a camp-out at A.W. ‘s parents’ property in Alba on Lake Fork. A.W. spent his day setting up a camper trailer, fishing and enjoying time with his family.

On Saturday night, Magdalene Steed, A.W. ‘s first wife, took a call from Carolyn McPherson, A.W. ‘s second wife. Carolyn told Magdalene that instead of joining the kids and grandkids at the lake, she and A.W. were staying behind in Sulphur Springs and would be down the next morning.

Magdalene said she assumed A.W. and Carolyn were headed to the VFW, as it was their usual hangout.

“She [Carolyn] called me the next morning [Sunday] and told me A.W. had just walked off,” Magdalene said. “They came in from the VFW about 1 a.m., I guess. He wanted to go gambling but she wanted to get in bed, so he supposedly just walked off.”

Magdalene says she did as Carolyn instructed her and notified the children and grandchildren A.W. would not be joining them.

A.W. was 53 years old at the time of his disappearance and was allegedly last seen by Carolyn at his home at 341 Woodcrest Drive in Sulphur Springs the early morning hours that Sunday.

He was wearing blue jeans, a western shirt, Redwing boots and a silver dollar belt buckle with "A.W." embossed on it. According to a 1989 Rains County Leader story, it was Carolyn who first reported A.W. missing on Aug. 31 to the Sulphur Springs Police Department.

CIRCUMSTANCES

At first, the SSPD considered A.W. ‘s disappearance to be a simple missing persons case, according to a 1988 edition of the News-Telegram. Magdalene stated A.W. told her shortly before his disappearance he was “more in debt than he had ever been before,” and as a man whose main focus was hard work at his tractor supply store in Emory, he liked to relax by shooting dice.

“He was a big gambler, huge gambler,” cousin Mike Nordin recently told the News-Telegram.

In addition, Magdalene said, A.W. told her that not long before his disappearance he caught Carolyn in the arms of another man. Nordin said he witnessed Carolyn’s liaison firsthand at the Sundance.

When Tuesday rolled around and his father didn’t show up at work, “I knew it was really time to start worrying,” son Gary Steed told the News-Telegram in 2007.

Gary described his father not only as his business partner at Steed’s Tractor and Equipment, but also as his best friend.

“I knew him well enough that he wouldn’t just go off and not call,” Gary told the Rains County Leader.

“I was married to him for nearly 25 years,” Magdalene agreed. “He wasn’t going to walk off.”

According to SSPD Detective Rusty Stillwagoner, A.W. has not used his social security number, drivers license or credit cards, which were on him at the time. He would be 86 years old in 2020.

“You just can’t get away. Not anymore, and not even then,” Nordin said. “He would have had to have money somehow.”

Furthermore, said Magdalene, as a lover of all things mechanical, A.W. was the proud owner of not one, but three trucks.

“I knew that wasn’t true,” Magdalene said. “He wouldn’t have left walking … he would have had one, probably all three keys, handy.”

And although he was a gambler, Magdalene said, “He always paid his bills.”

His son, Gary, agreed: “Anytime that he had lost, he always paid his debts. He didn’t gamble if he didn’t have the money.”

ANOMALIES

Shortly before his disappearance, A.W. allegedly told Magdalene he had discovered a large outstanding gambling debt Carolyn had racked up, she said. Magdalene contends this is corroborated by a $9,500 check cashed by First National Bank in Emory bearing A.W.’s signature, of which he allegedly had no knowledge, Magdalene said.

“This made his account overdrawn,” Magdalene wrote in a typed statement shortly after his disappearance. “They [the bank] called him, and he knew nothing about the check. Didn’t know the person the check was made out to or the third party that cashed the check.”

Magdalene said in her typed statement that A.W. signed a sworn statement that it was not his signature on the $9,500 check. The News-Telegram cannot verify the existence of the check or A.W.’s sworn statement, as Magdalene’s typed statement says the files now reside with the Texas Ranger Division.

A.W. allegedly communicated his frustrations about money to Magdalene in the days before his disappearance.

“He told me she [Carolyn Steed] wasn’t paying bills, so he needed my help to take her off the checking and off the credit cards,” Magdalene said. “He depended on me in that way because we were still friends.”

Then there were allegations of cheating. But, Magdalene said, “He still seemed to love her.”

“He told me, ‘I’m just trying to make it work as best I can,’” Magdalene said.

Thirty-six years after the fact, the News-Telegram cannot locate anyone who can place A.W. alive at the VFW on the evening of Aug. 31, 1986. A.W.’s signature allegedly appears in the VFW’s sign-in sheet, but family members say they’ve never seen it themselves.

After arriving home from the VFW, Carolyn allegedly later told Gary that she and A.W. had a fight about the dog making a mess on the bed. Magdalene’s notes from the time reflect that Carolyn allegedly told her A.W. “wanted to go to a dice game, and she refused to take him.” Whatever the case, all accounts from the time remain consistent: Carolyn told Gary, Magdalene and later SSPD that she last saw A.W. around 1 a.m. that morning, according to their accounts.

By the next morning around 7 or 8 a.m., Magdalene remembers, she received the call from Carolyn telling her A.W. had walked off. At first, she said, she didn’t think anything in particular, especially given A.W.’s supposed proclivity for late-partying.

“I told her, ‘Don’t worry about it,’” Gary remembers. “It wasn’t un-normal for him to go to a dice game and not get home until the next day.”

It seemed, though, that Carolyn had already called the police, Gary said. The News-Telegram could not locate the original call for service from 1986 to corroborate what time SSPD were called to Woodcrest Drive, but Magdalene remembers that it was “right away, because they told her not enough time had passed for him to be missing.”

On Tuesday, when Gary arrived to open the tractor supply store, a family business where A.W. and Carolyn worked as well, he said Carolyn was acting strangely.

“She come in asking if we’d seen him, wanting to hug us, and I just felt standoffish,” Gary said. “I didn’t want to think it, but I wanted to find out what did happen.”

At that point, Gary says, he made a trip from the tractor supply in Emory to his father’s home in Sulphur Springs — and what he saw alarmed him.

“All the furniture was up on the couches and the carpet was damp from shampoo and wet,” Gary said. “There were hampers and wet sheets, and all that didn’t quite make sense.”

As Gary made his way to the carport, where one of his father’s cars would be, Gary said he saw “oil, brand new oil poured out from one door to another with a floor-sweep put on.”

As a professional mechanic, Gary said he would never waste oil in such a way, and he said he doubts his father would either.

“I asked her [Carolyn] about that, and she said the kids were playing and threw it out,” he said. “But it was just perfectly poured out all the way around the car.”

STILL SEARCHING

In 1994, eight years after he disappeared, courts declared A.W. dead, according to original documentation. Gary says he has heard “every terrible thing” about where his father’s remains could be, from disposed in a wood-chipper to burned in a brush pile.

The family hired two different psychics, according to the Rains County Leader, who told them A.W.’s remains would be found somewhere near water. Gary still has both hand-sketched and printed maps where the family completed searches based on the psychics’ information. Magdalene can still recall a vivid dream where A.W. led her to his final resting place, and upon waking, she rushed there, only to find a home built in the spot.

The family still owns the little cabin in Alba where A.W. was supposed to join his children and grandchildren that holiday weekend, and his family still say they feel his absence acutely. One of A.W.’s trucks still sits in the driveway as if he’s about to return.

His machine shop became a space for family get-togethers. Across the road in a clearing in the oaks, a small circle of rocks has a headstone for A.W. with his date of birth and the last time he was seen alive.

The family donated a parcel of land next to their home where the Emory volunteer fire department built the Hoganville sub-station. A sign in large-print on the outside reads, “In memory of A.W. Steed.”

“We’ve gone just about as far as we know to go,” Gary said. “For many, many years, I’d be driving along, and it would all just hit me.”

“I understand the frustration,” Stillwagoner said. “They had a loved one that come up missing, and they couldn’t even bury him.”

By bringing up the case again, the family says, they have nothing to lose.

“I hope this does rattle some cages,” Nordin said. “I’d like to see some justice done. I wish his mom and dad had lived long enough to see justice come out of it.”

“I wish I could make it new,” Stillwagoner agreed. “There are things there probably could have been done in ‘86, but back then, we didn’t even have DNA [testing].

Even though A.W. and Magdalene had divorced prior to his disappearance, she still misses his friendship.

“We were friends,” she said. “I was 14 and he was 15. … There were three of us girls playing baseball out in the road, and we saw three boys riding down the road on bicycles. I said, ‘The one in the red shirt is mine.’ And he was, that was A.W.; that’s the way it went. We dated off and on, we dated other people, but we ended up together.”

For Nordin, he believes that regardless of what resolution may be, the family needs some answers.

“This has gone on for 30-plus years, and it shouldn’t have,” he said.